Featured Posts

- Index of Psychological Studies of Presidents and Other Leaders Conducted at the Unit for the Study of Personality in Politics

- The Personality Profile of U.S. Supreme Court Associate Justice Brett Kavanaugh

- The Leadership Style of North Korean Leader Kim Jong-un

- North Korea Threat Assessment: The Psychological Profile of Kim Jong-un

- Russia Threat Assessment: Psychological Profile of Vladimir Putin

- The Personality Profile of 2016 Republican Presidential Candidate Donald Trump

- Donald Trump's Narcissism Is Not the Main Issue

- New Website on the Psychology of Politics

- Unit for the Study of Personality in Politics --- 'Media Tipsheet'

categories

- Afghanistan (228)

- Al Gore (2)

- Amy Klobuchar (4)

- Ayman al-Zawahiri (7)

- Barack Obama (60)

- Ben Carson (2)

- Bernie Sanders (7)

- Beto O'Rourke (3)

- Bill Clinton (4)

- Bob Dole (2)

- Campaign log (109)

- Chris Christie (2)

- Chuck Hagel (7)

- Criminal profiles (8)

- Dick Cheney (11)

- Domestic resistance movements (21)

- Donald Trump (31)

- Economy (33)

- Elizabeth Warren (4)

- Environment (24)

- George H. W. Bush (1)

- George W. Bush (21)

- Hillary Clinton (9)

- Immigration (39)

- Iran (43)

- Iraq (258)

- Jeb Bush (3)

- Joe Biden (13)

- John Edwards (2)

- John Kasich (2)

- John Kerry (1)

- John McCain (7)

- Kamala Harris (5)

- Kim Jong-il (3)

- Kim Jong-un (11)

- Law enforcement (25)

- Libya (18)

- Mahmoud Ahmadinejad (6)

- Marco Rubio (2)

- Michael Bloomberg (1)

- Michele Bachmann (173)

- Mike Pence (3)

- Military casualties (234)

- Missing person cases (37)

- Mitt Romney (13)

- Muqtada al-Sadr (10)

- Muslim Brotherhood (6)

- National security (16)

- Nelson Mandela (4)

- News (5)

- North Korea (36)

- Osama bin Laden (19)

- Pakistan (49)

- Personal log (25)

- Pete Buttigieg (4)

- Presidential candidates (19)

- Religious persecution (11)

- Rick Perry (3)

- Rick Santorum (2)

- Robert Mugabe (2)

- Rudy Giuliani (4)

- Russia (7)

- Sarah Palin (7)

- Scott Walker (2)

- Somalia (20)

- Supreme Court (4)

- Syria (5)

- Ted Cruz (4)

- Terrorism (65)

- Tim Pawlenty (8)

- Tom Horner (14)

- Tributes (40)

- Uncategorized (50)

- Vladimir Putin (4)

- Xi Jinping (2)

- Yemen (24)

Links

archives

- November 2021

- January 2021

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- October 2019

- July 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- July 2010

- June 2010

- May 2010

- April 2010

- March 2010

- February 2010

- January 2010

- December 2009

- November 2009

- October 2009

- September 2009

- August 2009

- July 2009

- June 2009

- May 2009

- April 2009

- March 2009

- February 2009

- January 2009

- December 2008

- November 2008

- October 2008

- September 2008

- August 2008

- July 2008

meta

‘Master of the Mind’ Theodore Millon, Scholar of Personality and Its Disorders, Dies at 85

Theodore Millon, a Student of Personality, Dies at 85

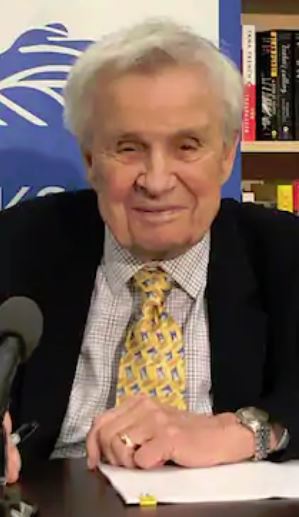

Theodore Millon (Photo: The New York Times)

By Benedict Carey

February 1, 2014

Theodore Millon, a psychologist whose theories helped define how scientists think about personality and its disorders, and who developed a widely used measure to analyze character traits, died on Wednesday [Jan. 29, 2014] at his home in Greenville Township, N.Y. He was 85.

The cause was complications of heart disease, his granddaughter Alyssa Boice said.

Dr. Millon (pronounced “Milan,†like the city in Italy) learned about the oddities of personality at first hand, by wandering the halls of Allentown State Hospital, a mental institution, after being named to the hospital’s board in the 1950s as a part an overhaul effort in Pennsylvania. A young assistant professor at nearby Lehigh University at the time, he “frequently ventured incognito through the hospital,†he wrote in an essay in 2001, “at times clothed in typical hospital garb overnight or for entire weekend periods, conversing at length with patients housed in a variety of acute and chronic wards.â€

At the University of Illinois in the 1970s, he began to think and write more deeply about the patterns underlying specific character types that therapists had described: the narcissist, with fragile, grandiose self-approval; the dependent, with smothering clinginess; the histrionic, always in the thick of some drama, desperate to be the center of attention. By 1980, he had pulled together the bulk of the work on such so-called personality disorders, most of it descriptive, and turned it into a set of 10 standardized types [link added] for the American Psychiatric Association’s third diagnostic manual [DSM-III, Axis II].

Along the way he developed the Millon Clinical Multiaxial Inventory (MCMI), which became the most commonly used diagnostic assessment for personality problems. It is still widely used today, in its third edition, the MCMI-III.

“He was a monumental figure in shaping the understanding of personality disorders,†said Thomas Widiger, a professor of psychology at the University of Kentucky. “Prior to Ted, there wasn’t any measure to speak of. He just dominated the field during a key period of its growth.â€

Theodore Millon was born in Manhattan on Aug. 18, 1928, the only child of Abner Millon, a tailor, and the former Mollie Gorkowitz. He grew up in the Bensonhurst neighborhood of Brooklyn and graduated from Lafayette High School in 1945 before earning bachelor’s degrees in psychology, physics and philosophy at City College of New York. After graduating in 1950, he earned a Ph.D. from the University of Connecticut in 1953, the year after he married Renée Baratz. She survives him, as do three daughters, Diane Bobb, Dr. Carrie Millon [link added] and Adrienne Hemsley; a son, Andy; and eight grandchildren.

Loquacious and opinionated, Dr. Millon, who described himself as an exemplar of “secure narcissism,†became a kind of institution unto himself after laying a foundation for the study of personality disorders. He left the University of Illinois for the Coral Gables campus of the University of Miami, where — between visiting professorships at Harvard and McLean Hospital — he founded the Institute for Advanced Studies in Personology and Psychopathology, a platform to advance his ideas, publishing analyses, books and various personality assessments.

Dr. Millon wrote more than 25 books and co-wrote more than 50 academic papers. The American Psychological Association awarded him its Gold Medal Award for Lifetime Achievement in 2008.

In one of his books, an encyclopedia of behavioral scientists called “Masters of the Mind†(2004), he included an entry for “Theodore Millon (1928 — ).†Dr. Millon, he wrote of himself, was distinguished from many others in the book “by the fact that he appears, contrawise, to be invariably buoyant, if not jovial. Critics are not invariably enamored, however, finding his work to be, at times, too speculative, his writing unduly imaginative, and his creativity overly expansive.â€

———

A version of this article appeared in print on February 1, 2014, on page A21 of the New York edition with the headline: Theodore Millon, a Student of Personality, Dies at 85.

———

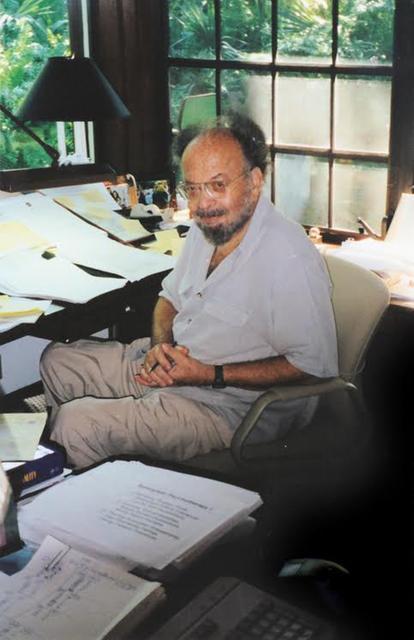

Theodore Millon at his favorite desk. (Photo courtesy of the Millon family)

By Howard Cohen

![]()

January 31, 2014

Theodore Millon’s most significant memory of his youth, he wrote in a 2001 autobiography for his family, instigated by the events of 9/11, was one of familial warmth.

Millon, a major figure in the field of psychology and the treatment of personality disorders, wrote: “[It] was my father’s all-consuming affection for me (the roots of my secure narcissism, I am sure), most charmingly illustrated by the fact that he brought home a gift for me (toy, game, book) every working day from the time I was 2 until I turned 13.â€

Millon, who died Wednesday [Jan. 29, 2014] at his home in Greenville Township, N.Y., at age 85, was born in Manhattan as the only child to immigrant parents from Lithuania and Poland and raised in Bensonhurst, Brooklyn. He would use these memories of his formative years in the development of diagnostic questionnaire tools such as the Millon Clinical Multiaxial Inventory and earlier versions of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.

Assessment tools

These psychological assessment tools, for which he was a key contributor during his tenure with the Neuropsychiatric Institute of the University of Illinois Medical Center in Chicago in the late 1960s and ‘70s, are still used by clinicians and researchers, along with psychiatric drug regulation agencies and pharmaceutical companies, the health insurance industry and the legal system to classify and understand various disorders.

“The profession’s acceptance of my upgraded assessment tools, especially the MCMI-III, has been exceptionally gratifying,†he wrote in his autobiography. “It ranks now second only to the MMPI (Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory) and the Rorschach as the most frequently employed of the psychodiagnostic tools in this country.â€

University of Miami

Millon, who moved to Coral Gables in the late ‘70s, would enjoy a lengthy run as clinical psych director at the University of Miami “as a retirement position†beginning in 1977, but he was customarily productive. Along with Neil Schneiderman, a physiological psychologist, he established a doctoral clinical health psychology program at UM.

He was also a senior scientific scholar emeritus at the Institute for Advanced Studies in Personality and Psychopathology, and through his five-decade career taught at Lehigh and the University of Illinois and was a visiting professor at Harvard Medical School. He published more than 25 books, including his favorite, Masters of the Mind: Exploring the Story of Mental Illness from Ancient Times to the New Millennium (Wiley; $35), for which he led a reading at Coral Gables’ Books & Books in 2004. He earned his PhD from the University of Connecticut.

“Teaching became my professional raison d’être, one which I loved from the start and one I continue to cherish to this waning day of my academic career,†he wrote in 2001.

Daughter Carrie Millon, of Pinecrest, followed her father’s lead into the field of psychology and worked with him at UM.

Arts passion

“He was an incredible man in so many ways,†she said. “You’re not supposed to brag … but what a brilliant, brilliant mind. He was the prototypical renaissance man.â€

That’s because Millon was passionate about the arts, too. He loved acting, singing, painting, sculpting and was an art collector and classical music aficionado.

During high school, and as an undergrad at City College of New York, he was tempted into a theatrical or singing career — he sang with crooner Vic Damone and, as a kid, was best buddies with Maurice Sendak, an illustrator who would go on to fame with his children’s books, including Where the Wild Things Are, and the 1975 animated TV musical Really Rosie with songwriter Carole King. These artsy vocations, his parents told him, were not befitting “a nice Jewish boy.†Academia and the field of psychology would have to do.

But what fun he had in that Bensonhurst neighborhood. He wrote of sharing “Harry Potter-like†adventures on the front steps of his friends’ homes. These pals included Sendak and Wally, the only African-American youngster in their neighborhood and Marvin, a quiet and intelligent boy with a severe speech and hearing impairment.

“Both were persona non-grata kids, poked fun at or completely shunned by both local peers and adults,†he remembered. “It was not any humanistic impulse or deviance on my part that drew me to them; I simply found both interesting and thoughtful peers.â€

Legacy

Carrie Millon says that that love has been returned to the family in the numerous calls and correspondence that arrived from former students who learned that Millon’s health was failing.

“We’ve had such an incredible outpouring of support from all over the place,†she said. “His greatest legacy was his students. And in every single letter we received, every one of them said, ‘You’re like a father to me.’ He was an incredibly generous man and that’s coming back to us in droves.â€

Millon is survived by his wife, Renée, whom he married in 1952, their children Diane Bobb, Carrie Millon, Andrew Millon, Adrienne Hemsley, eight grandchildren, five great-grandchildren and a niece and nephew. Services will be at 1 p.m. Sunday at Temple Sinai, 75 Highland Ave., Middletown, NY.

The family would like to place a bench in Millon’s honor in Central Park. To make a donation, instead of flowers, write Central Park Conservancy, Attn: Adopt-a-Bench, 14 E. 60th St., New York, NY 10022 and cite Theodore Millon Bench.

——————

Dr. Theodore Millon, Ph.D., D.Sc.

August 18, 1928 — January 29, 2014

Greenville Township, NY

Leading Personality Theorist and Psychologist, Dr. Theodore Millon, passed away on January 29, 2014, at his home in Greenville Township, NY, after a remarkable life.

Dr. Millon was the author of over 25 books and the developer of numerous highly regarded diagnostic inventories including the MCMI. He was a key member of the DSM-III task force and of the DSM-IV’s workgroup on personality disorders. Dr. Millon was a Senior Scientific Scholar Emeritus at the Institute for Advanced Studies in Personality and Psychopathology, having served previously over a fifty-year sequence of professorial appointments at Lehigh, University of Illinois, University of Miami and Harvard. He received over twenty lifetime achievement awards, including APF’s Gold Medal for Lifetime Achievement in Applied Research, APA’s Distinguished Award for Applied Psychological Science, as well as its 2000 Presidential Citation.

Theodore was born in Manhattan on August 28, 1928 to Abner and Mollie (Gorkowitz) Millon. He was raised in Bensonhurst, Brooklyn where he graduated from Lafayette High School in 1945. He earned his BA from the City College of New York ’49 and his Ph.D. from the University of Connecticut ’52 and later received an Honorary Doctorate from the Free University of Brussels ’94.

He had a keen interest in art and was a man of many talents and interests. He loved acting and singing and was a painter, sculptor and collector of art. Dr. Millon was a classical music aficionado, followed professional sports and studied physics as a hobby.

In 1952 he married Renée Baratz. Although he was an admirable scholar, his role as a husband, father and grandfather was just as important to him. He was a kind, loving and generous man who cared deeply for his family. He is predeceased by his parents. In addition to his wife, he is survived by his children, Diane Bobb (Allen) of Greenville, NY; Dr. Carrie Millon of Pinecrest, FL; Andy Millon of Brooklyn, NY; Adrienne Hemsley (Martin) of White Plains, NY; a niece, Linda Shultz (David); a nephew, David Grabel; his grandchildren: Alyssa Boice (Rory), Katherine Sinsabaugh (Joseph), Molly Niedbala, Olivia Niedbala, Elizabeth Levin, Matthew Hemsley, Annie Hemsley, William Hemsley, and five great-grandchildren. He will not only be missed by his family, but by the many colleagues and students whose lives he influenced. His legacy was far reaching and will carry on. The family would also like to thank his caregivers, Leila Agustin and Elizabeth Grennille, for extending his life and bringing him great comfort.

A private memorial service will be held. In lieu of flowers, those wishing to make a donation may do so to the Central Park Conservancy, Attn: Adopt-A-Bench, 14 East 60th Street, New York, NY 10022. Please write “Theodore Millon Bench” in the memo line, or call 212-310-6617.

———————————

PHOTO GALLERY

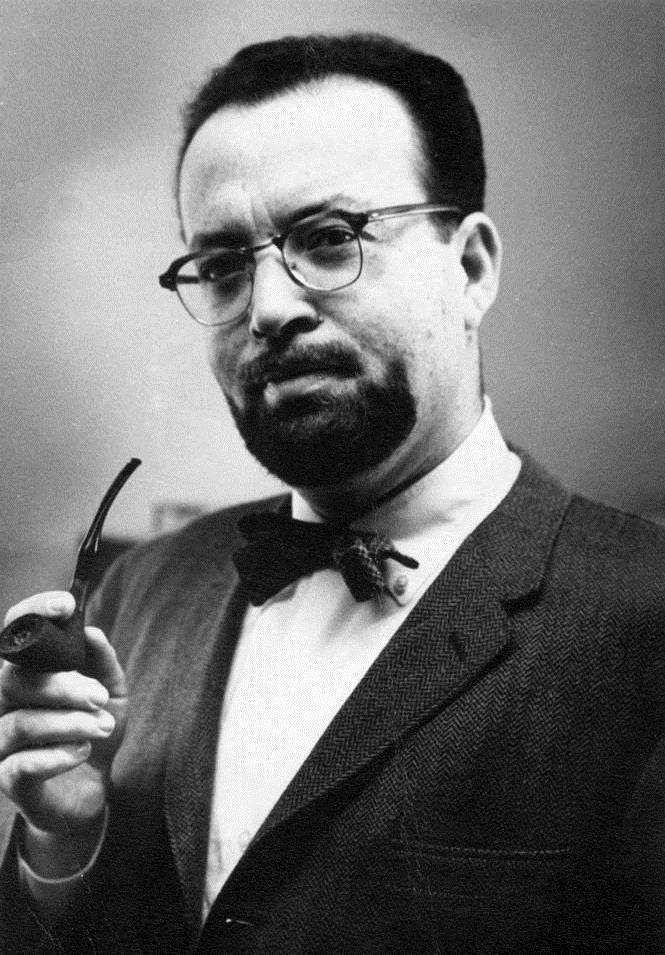

Ted Millon as a young professor in 1962.

(Photo courtesy of Theodore Millon)

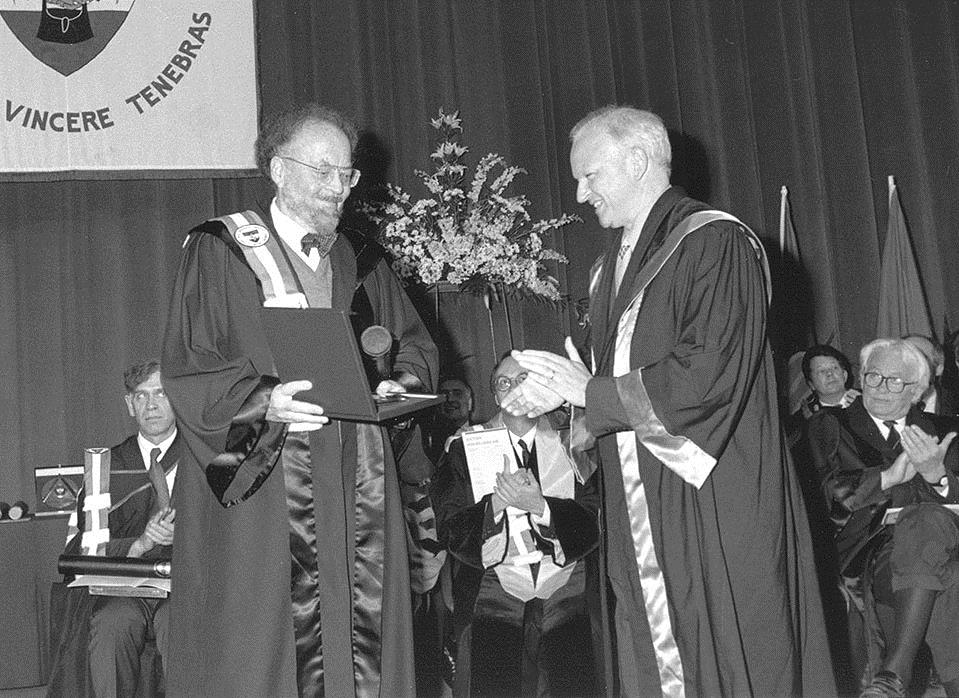

Theodore Millon receives an honorary Doctor of Science degree from Dean Hedwig Sloore at the Free University of Brussels, 1994. (Photo courtesy of Theodore Millon)

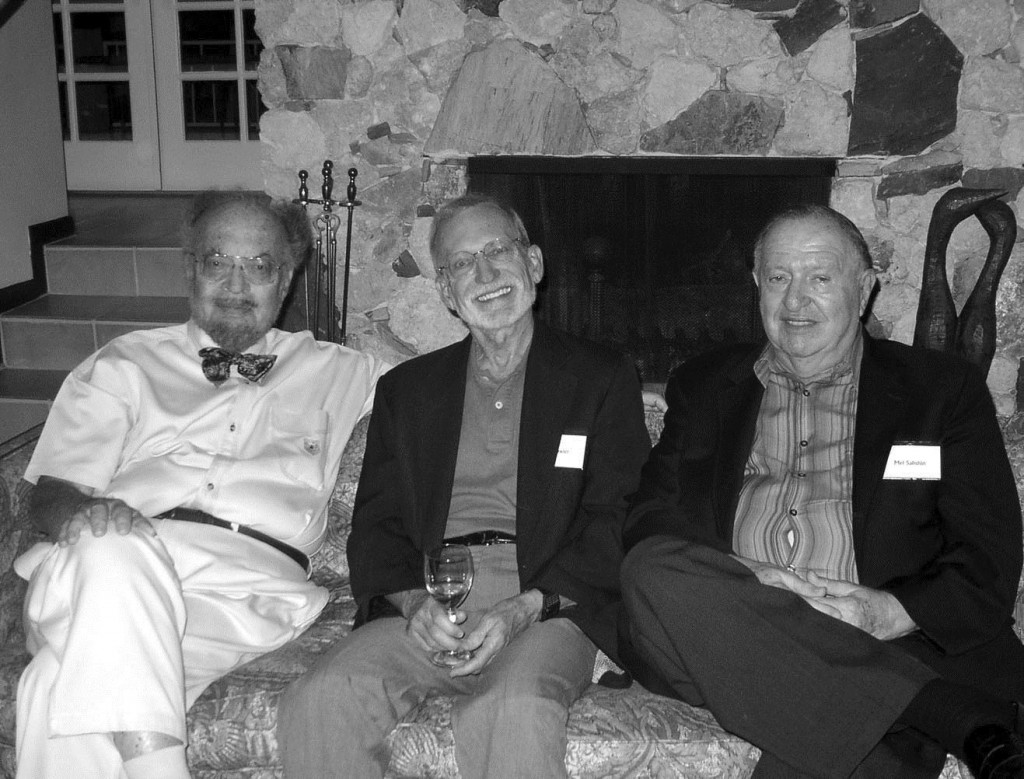

Ted Millon, Ray Fowler (Executive Director Emeritus of the American Psychological Association), and Mel Sabshin (Medical Director Emeritus of the American Psychiatric Association) during Millon’s Festschrift weekend, Miami, Oct. 2003. (Photo courtesy of Theodore Millon)

Dr. Theodore Millon receives the Gold Medal Award for Lifetime Achievement in the Application of Psychology at the 2008 annual meeting of the American Psychological Association in Boston, Mass.

—————————————

——————————————————

PERSONAL REMINISCENCES

Aubrey Immelman and Ted Millon, October 17, 2002.

Immelman, A., & Millon, T. (2003, June). A research agenda for political personality and leadership studies: An evolutionary proposal. Unpublished manuscript, Unit for the Study of Personality in Politics, St. John’s University and the College of St. Benedict, Collegeville and St. Joseph, MN. Retrieved from Digital Commons website: http://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/psychology_pubs/124/

RELATED TRIBUTE

James MacGregor Burns, Scholar of Presidents and Leadership, Dies at 95

Historian James MacGregor Burns at his home in Williamstown, Mass., in 2007.

(Photo credit: Nathaniel Brooks / Associated Press via The New York Times)

By Bruce Weber

![]()

July 16, 2014

James MacGregor Burns, a Pulitzer Prize-winning biographer and political scientist who wrote voluminously about the nature of leadership in general and the presidency in particular, died on Tuesday [July 15, 2014] at his home in Williamstown, Mass. He was 95.

The historian Michael Beschloss, a friend and former student, confirmed the death.

Mr. Burns, who taught at Williams College for most of the last half of the 20th century, was the author of more than 20 books, most notably “Roosevelt: The Soldier of Freedom†(1970), a major study of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s stewardship of the country through World War II. It was awarded both the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award.

An informal adviser to presidents, Mr. Burns was a liberal Democrat who once ran for Congress from the westernmost district of Massachusetts. Though he sometimes wrote prescriptively from — or for — the left, over all he managed the neat trick of neither hiding his political viewpoint in his work nor funneling his work through it.

Mr. Burns had unrestricted access to John F. Kennedy.

(Photo credit: William H. Tague via The New York Times)

His work was often critical of American government and its system of checks and balances, which in his view had become an obstacle to visionary progress, particularly when used by a divided or oppositional Congress as a rein on the presidency. In works like “The Deadlock of Democracy†(1963) and “Packing the Court: The Rise of Judicial Power and the Coming Crisis of the Supreme Court†(2009), he argued for systemic changes, calling for a population-based Senate, term limits for Supreme Court justices and an end to midterm elections.

The nature of leadership was his fundamental theme throughout his career. In his biographies of Roosevelt, John F. Kennedy and Edward M. Kennedy, among others, and in his works of political theory — including “Leadership,†a seminal 1978 work melding historical analysis and contemporary observation that became a foundation text for an academic discipline — Mr. Burns focused on parsing the relationship between the personalities of the powerful and the historical events they helped engender.

His award-winning Roosevelt biography, for example, was frank in its admiration of its subject. But the book nonetheless distilled, with equal frankness, Roosevelt’s failings and character flaws; it faulted him for not seizing the moment and cementing the good relations between the United States and the Soviet Union when war had made them allies. This lack of foresight, Mr. Burns argued, was a primary cause of the two nations’ drift into the Cold War.

Roosevelt “was a deeply divided man,†he wrote, “divided between the man of principle, of ideals, of faith, crusading for a distant vision, on the one hand; and, on the other, the man of Realpolitik, of prudence, of narrow, manageable, short-run goals, intent always on protecting his power and authority in a world of shifting moods and capricious fortune.â€

This was typical of Mr. Burns, who wrote audaciously, for a historian, with an almost therapistlike interpretation of the historical characters under his scrutiny and saw conflict but no contradiction in the conflicting and sometimes contradictory impulses of great men. He could admire a president for his politics and his leadership skills, yet report on his inherent shortcomings, as he did with Roosevelt; or spot a lack of political courage that undermined a promising presidency, as he did with President Bill Clinton and his vice president, Al Gore, in “Dead Center: Clinton–Gore Leadership and the Perils of Moderation,†written with Georgia Jones Sorenson. In the book, he chastised both men for yielding their liberal instincts too easily.

In “The Power to Lead: The Crisis of the American Presidency,†his 1984 book about the dearth of transforming leaders, as opposed to transactional ones, in contemporary America, Mr. Burns was able to denounce the outlook of a staunch conservative like President Ronald Reagan but admire him for his instinctive leadership — his understanding of not just how to maneuver the levers of power but also how to muster party unity and effect an attitudinal shift in society.

This distinction between transforming and transactional leadership was central to Mr. Burns’s political theorizing. As he explained it in “Leadership,†the transactional leader is the more conventional politician, a horse trader with his followers, offering jobs for votes, say, or support of important legislation in exchange for campaign contributions.

The transforming leader, on the other hand, “looks for potential motives in followers, seeks to satisfy higher needs, and engages the full person of the follower,†Mr. Burns wrote.

“The result of transforming leadership,†he went on, “is a relationship of mutual stimulation and elevation that converts followers into leaders and may convert leaders into moral agents.â€

If there was any way in which Mr. Burns’s personal views pierced his objectivity as a writer and researcher, it was in his understanding of the human elements of leadership. He had faith in the potential for human greatness, and though he often scolded presidents, congressmen and party officials for failing to strive for progress, one could discern in his writing a pleading for great men and women to lead with greatness.

“That people can be lifted into their better selves,†he wrote at the end of “Leadership,†“is the secret of transforming leadership and the moral and practical theme of this work.â€

Mr. Burns was born on Aug. 3, 1918, in Melrose, Mass., outside Boston. His father, Robert, a businessman, and his mother, the former Mildred Bunce, came from Republican families, though Mr. Burns described her as holding feminist principles. She largely raised him, in Burlington, Mass., after his parents’ divorce, and it was she, he said, who instilled in him the independence of mind to oppose the political views prevalent in his father’s family.

“I rebelled early,†Mr. Burns told the television interviewer Brian Lamb in 1989. “I got a lot of attention simply because I sat at the dinner table making these outrageous statements that they never heard anybody make face to face.†He added, “There was a lot of very strenuous and sometimes angry debate within the household.â€

After graduating from Williams, Mr. Burns went to Washington and worked as a congressional aide. He served as an Army combat historian in the Pacific during World War II, receiving a Bronze Star, and afterward earned a Ph.D. from Harvard. He did postdoctoral work at the London School of Economics. His first book, “Congress on Trial: The Legislative Process and the Administrative State,†a critical appraisal of American lawmaking, was published in 1949.

After his second book, “Roosevelt: The Lion and the Fox†(1956), a study of the president’s early years, Mr. Burns ran for Congress in 1958 from a western Massachusetts district that had not elected a Democrat since 1896 — and it did not again.

During the campaign he became acquainted with John F. Kennedy, then running for his second term as senator from Massachusetts. After the election, with unrestricted access to Kennedy, his staff and his records, he wrote “John Kennedy: A Political Profile,†an assessment of him as a potential president. Though the book was largely favorable, it was not the hagiography the Kennedy family and presidential campaign had anticipated. (“I think you underestimate him,†Jacqueline Kennedy wrote to him after she read it, adding: “Can’t you see he is exceptional?â€)

After Kennedy’s assassination, Mr. Burns said frequently that Kennedy had been a great leader and would have been even greater had he lived. But in his book he called Kennedy “a rationalist and an intellectual†and questioned whether he had the character strength to exert what he called “moral leadership.â€

“What great idea does Kennedy personify?†he wrote. “In what way is he a leader of thought? How could he supply moral leadership at a time when new paths before the nation need discovering?â€

In 1978, after a half-dozen more books, including the second Roosevelt volume and separate studies of the presidency and of state and local governments, Mr. Burns wrote “Leadership,†an amalgamation of a lifetime of thinking about the qualities shared and exemplified by world leaders throughout history. It became a standard academic text in the emerging discipline known as leadership studies, and Mr. Burns’s concept of transforming leadership itself became the subject of hundreds of doctoral theses.

“It inspires our work,†Georgia Sorenson, who founded the Center for Political Leadership and Participation at the University of Maryland, said of “Leadership.†She persuaded Mr. Burns, who was on her dissertation committee, to teach there in 1993, and four years later the university renamed the center in his honor; it is now an independent nonprofit organization, the James MacGregor Burns Academy of Leadership.

Mr. Burns’s two marriages ended in divorce. He is survived by three children and his companion, Susan Dunn, with whom he collaborated on “The Three Roosevelts†and a biography of George Washington, two of the half-dozen or so books Mr. Burns wrote or co-wrote after the age of 80. His last book, “Fire and Light: How the Enlightenment Transformed Our World,†was published in 2013.

Asked to describe Mr. Burns’s passions away from his writing, Ms. Sorenson named skiing; his two golden retrievers, Jefferson and Roosevelt; the blueberry patch in his yard; and his students.

“He would never bump a student appointment to meet with someone more important,†Ms. Sorenson said. “I remember Hillary Clinton once inviting him to tea, and he wouldn’t go because he had to meet with a student. And he would never leave his place in Williamstown during blueberry season.â€

A version of this article appears in print on July 16, 2014, on page A20 of the New York edition with the headline: James MacGregor Burns, Scholar of Leaders and Leadership, Dies at 95.

Read the obituary in The New York Times

RELATED TRIBUTE

Jerrold Post, Pioneer in Political Psychology Profiling, Dies of Covid-19

CIA psychological profiler who labeled Trump ‘dangerous’ dies of Covid-19

Jerrold M. Post, 86, a psychiatrist who worked for the CIA producing psychological profiles of foreign leaders such as Saddam Hussein, died of Covid-19 a year after publishing a book about President Trump. (Family photo / The Washington Post)

By Sydney Trent

![]()

December 6, 2020

As a pioneering psychological profiler for the Central Intelligence Agency and later as a consultant, Jerrold M. Post plumbed the lives, leadership styles and, at times, the mental illness of foreign heads around the globe. Over decades, his expertise and instincts were greatly in demand, especially at the White House.

The Yale- and Harvard-trained psychiatrist advised former president Jimmy Carter about how best to negotiate with Menachem Begin and Anwar Sadat before the Camp David Peace Accords. He explained Sadat’s “Nobel Prize Complex†— his desire to be remembered as a great leader — and Begin’s biblical preoccupation and obsession with detail.

Post warned about labeling Saddam Hussein simply as “the mad man of the Middle East,†lest it mislead political leaders into thinking Hussein was unpredictable, when in fact he was not. As an expert in the psychology of terrorism, Post produced psychological profiles of suicide bombers in Israel and opined on the corporate leadership style of al-Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden.

And yet in late 2019 — a year before his death on Nov. 22 of covid-19 at the age of 86 — Post found himself doing what at one point would have been unthinkable: publishing a book about the alarming psychological makeup of an American president.

In writing “Dangerous Charisma: The Political Psychology of Donald Trump and His Followers,†Post risked violating the American Psychiatric Association’s “Goldwater Rule,†which forbids the diagnosis of public figures without full evaluation and consent.

“He was a Life Fellow of the APA, but he said if they kicked him out, he didn’t care,†said his wife, Carolyn Post. “He felt it was that important and that psychiatrists have a duty to warn.â€

By then, Post had had a storied two-decade career as founding director of the CIA’s Center for the Analysis of Personality and Political Behavior. He then used his expertise to found Political Psychology Associates, a research and consulting firm that specialized in industrial espionage, counterterrorism and leadership assessment. All along, he lectured as a professor at George Washington University, wrote 14 books and continued to see patients in a private practice he ran out of the basement of his Bethesda home.

His career success, his family said, was a reflection of an insatiable, roving curiosity and a probing empathy for his fellow humans — qualities that also made him a highly engaging friend and a nurturing husband, father and doctor.

He devoured books about politics and history, with a penchant for biographies by Doris Kearns Goodwin and David McCullough. He traveled the world with his family and — always drawn to the human — took lovely candid photographs of people off the beaten path that won national awards, his family said. He did not hang back as tourists tend to, but engaged people in his humble way about their lives. On a trip to Mexico with his daughter Cindy Post he drove off the main road, where he came upon some male villagers playing a board game near a cliff overlooking the ocean. He gestured to join them, they offered drinks, and he snapped away.

“He always wanted to know, what are the people about and what is their world?†said Cindy, 58, a clinical psychologist in Silver Spring. Her father “was kind of a whirling dervish. . . . He was the kind of person who would think, ‘There are 24 hours in a day. Can we fill 23 of them?â€

He zipped from place to place in his beloved convertible sports cars — a favorite was a green Austin-Healey — with a signature driving cap atop his head.

Post was born in 1934 in New Haven, Conn. His father sold movies to theaters and his mother worked as a bookkeeper, taught painting, and made and sold pottery. He put himself through nearby Yale University for his undergraduate degree and then medical school. He received his postgraduate psychiatric training at Harvard Medical School and the National Institute of Mental Health.

He was an accomplished improvisational jazz pianist who could also play almost any tune by ear, his family said. For anniversaries, birthdays and other special occasions, he would write new lyrics for Gilbert and Sullivan show tunes and, with Carolyn, serenade friends and relatives.

He was witty, too, and loved word play. Post was a member of a lunch group of GWU professors dubbed IOTA, which stood for the International Order of Twisted Aphorisms. Members would write puns and aphorisms to bring to the meetings. When a nurse asked him before the recent election who the president was — standard practice with elderly patients — he replied sardonically: “Unfortunately, we don’t have one at the moment.â€

Post was a fiercely competitive backgammon player — and schooled his daughter Meredith Gramlich from childhood on the fine points of the game on a custom hand-carved board from Israel. In the twilight of his life, he reassured 52-year-old Gramlich proudly, “I never threw a game for you.â€

He was also a faithful father to daughter Kirsten Davidson, 49, who is blind and intellectually disabled, greeting her in a special way every morning and signing off to her each night.

At the CIA, Post was able to marry his triple passions of psychiatry, history and politics by founding the agency’s Center for the Analysis of Personality and Political Behavior. The work of the center, an interdisciplinary behavioral sciences unit that assessed foreign leaders for the president and other senior officials, was groundbreaking, said Nicholas Dujmovic, a longtime CIA historian who retired from the agency in 2016 and is now an assistant professor of politics at Catholic University of America.

“Post made it obvious through his work that we need to have professionals involved in assessing the health and psychology of foreign leaders,†said Dujmovic, who as an editor of the president’s daily briefings at the CIA said he frequently encountered Post’s “legacy†in briefing contributions.

He said he was surprised to learn that among Post’s many honors — including the Intelligence Medal of Merit in 1979 after his role in the Camp David Accords — he is not listed as one of the CIA “Trailblazers,†who made a significant impact on the agency’s history. He believes that could be due to “snobbery†within the agency during Post’s time there that distrusted the practice of psychological analysis, especially when conducted from afar.

President Carter contradicted that notion, Dujmovic noted, openly crediting the role of Post’s team in the success of the historic peace agreement. Carter “basically said ‘I spent two weeks with these men and I wouldn’t change a word of [Post’s] assessments,’ †Dujmovic said.

In his last effort to psychologically profile a leader, Post trained his expertise on Donald Trump. In “Dangerous Charisma,†co-authored with Stephanie Doucette, Post described Trump as a destructive charismatic leader with the traits of a classic narcissist — such as grandiosity, lack of empathy, hypersensitivity to criticism and no constraints of conscience. But Post also probed Trump’s symbiotic relationship with his followers, and theirs with him.

“The dangerous, destructive charismatic leader polarizes and identifies an outside enemy and pulls his followers together by manipulating their common feelings of victimization,†Post said in a December 2019 interview.

Were he to lose the election, Post said a year ago, “I think we can be assured that he will not concede early. Trump may not even recognize the legitimacy of the election.â€

After the book’s publication, Post’s health took a downward turn. His kidneys had already been failing, forcing him to go for dialysis several times a week, when he suffered a stroke in July. After several months in a rehabilitation facility, Post spent his final weeks of life surrounded by family at home. On Sunday Nov. 15, he began having trouble breathing. Carolyn called 911 and an ambulance rushed him to the hospital, where he tested positive for the coronavirus. He died exactly one week later.

Visiting with her father in his waning days, Cindy Post said, she tried to help him consider the fullness of his restless life and find peace with the end.

“How do you feel about the life you had,†she asked him. “You’ve done a lot of things, you know.â€

“There’s so much more to do,†Post replied.

“But can you let this be enough?†his daughter asked.

He didn’t answer, but Cindy said she could see the frustration written on her father’s face.

—————————

Related report

Jerrold Post, CIA psychiatrist who profiled Trump, dies of Covid aged 86 (Amanda Holpuch, The Guardian, Dec. 6, 2020)

Jerrold Post with his dog, Coco. (Photo: Jocelyn Augustino / The Guardian)

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

March 9th, 2015 at 1:00 am

[…] Last fall, my student Avà Bahadoor and I conducted a study of the political personality of Hillary Clinton. We collected personal data from published biographical materials and political reports, and synthesized these public records into a personality profile using the second edition of the Millon Inventory of Diagnostic Criteria (MIDC), which I adapted from the work of contemporary personality theorist Theodore Millon. […]

October 8th, 2016 at 6:15 pm

[…] A simplified explanation of temperament, paraphrasing psychologist Theodore Millon, would be that “temperament” refers to a person’s typical manner of displaying emotion and the predominant character of an individual’s affect (i.e., emotion), and the intensity and frequency with which he or she expresses it. […]

October 8th, 2016 at 6:57 pm

[…] According to psychologist Theodore Millon, Ph.D., a leading expert on personality and its disorders, the “distinctive feature” of the Ambitious-Outgoing personality composite, which he labeled the “amorous narcissist,” is an “erotic and seductive orientation.” […]

February 21st, 2017 at 11:21 pm

[…] An indirect personality assessment of Donald Trump conducted from the conceptual perspective of Theodore Millon revealed that Trump’s predominant personality patterns are Ambitious/exploitative (Scale 2: a measure of narcissistic tendencies) and Outgoing/impulsive (Scale 3: a measure of histrionic tendencies), infused with secondary features of the Dominant/controlling pattern (Scale 1A: a measure of sadistic tendencies) and supplemented by a Dauntless/adventurous tendency (Scale 1B: a measure of antisocial and sensation-seeking tendencies). […]

February 11th, 2020 at 5:35 am

[…] Last fall, my student Avà Bahadoor and I conducted a study of the political personality of Hillary Clinton. We collected personal data from published biographical materials and political reports, and synthesized those public records into a personality profile using the second edition of the Millon Inventory of Diagnostic Criteria (MIDC), which I adapted from the work of contemporary personality theorist Theodore Millon. […]

August 18th, 2020 at 12:31 am

[…] The poster presents the results of an indirect assessment of the personality of former U.S. vice president Joe Biden, Democratic nominee in the 2020 U.S. presidential election, from the conceptual perspective of personologist Theodore Millon. […]

September 5th, 2020 at 1:11 am

[…] The poster presents the the results of an indirect assessment of the personality of U.S. senator Kamala Harris, Democratic vice-presidential nominee in the 2020 U.S. presidential election. […]

October 3rd, 2020 at 6:49 am

[…] The research paper presents the results of an indirect assessment of the personality of U.S. vice president Mike Pence, from the conceptual perspective of personologist Theodore Millon. […]