Featured Posts

- Index of Psychological Studies of Presidents and Other Leaders Conducted at the Unit for the Study of Personality in Politics

- The Personality Profile of U.S. Supreme Court Associate Justice Brett Kavanaugh

- The Leadership Style of North Korean Leader Kim Jong-un

- North Korea Threat Assessment: The Psychological Profile of Kim Jong-un

- Russia Threat Assessment: Psychological Profile of Vladimir Putin

- The Personality Profile of 2016 Republican Presidential Candidate Donald Trump

- Donald Trump's Narcissism Is Not the Main Issue

- New Website on the Psychology of Politics

- Unit for the Study of Personality in Politics --- 'Media Tipsheet'

categories

- Afghanistan (228)

- Al Gore (2)

- Amy Klobuchar (4)

- Ayman al-Zawahiri (7)

- Barack Obama (60)

- Ben Carson (2)

- Bernie Sanders (7)

- Beto O'Rourke (3)

- Bill Clinton (4)

- Bob Dole (2)

- Campaign log (109)

- Chris Christie (2)

- Chuck Hagel (7)

- Criminal profiles (8)

- Dick Cheney (11)

- Domestic resistance movements (21)

- Donald Trump (31)

- Economy (33)

- Elizabeth Warren (4)

- Environment (24)

- George H. W. Bush (1)

- George W. Bush (21)

- Hillary Clinton (9)

- Immigration (39)

- Iran (43)

- Iraq (258)

- Jeb Bush (3)

- Joe Biden (13)

- John Edwards (2)

- John Kasich (2)

- John Kerry (1)

- John McCain (7)

- Kamala Harris (5)

- Kim Jong-il (3)

- Kim Jong-un (11)

- Law enforcement (25)

- Libya (18)

- Mahmoud Ahmadinejad (6)

- Marco Rubio (2)

- Michael Bloomberg (1)

- Michele Bachmann (173)

- Mike Pence (3)

- Military casualties (234)

- Missing person cases (37)

- Mitt Romney (13)

- Muqtada al-Sadr (10)

- Muslim Brotherhood (6)

- National security (16)

- Nelson Mandela (4)

- News (5)

- North Korea (36)

- Osama bin Laden (19)

- Pakistan (49)

- Personal log (25)

- Pete Buttigieg (4)

- Presidential candidates (19)

- Religious persecution (11)

- Rick Perry (3)

- Rick Santorum (2)

- Robert Mugabe (2)

- Rudy Giuliani (4)

- Russia (7)

- Sarah Palin (7)

- Scott Walker (2)

- Somalia (20)

- Supreme Court (4)

- Syria (5)

- Ted Cruz (4)

- Terrorism (65)

- Tim Pawlenty (8)

- Tom Horner (14)

- Tributes (40)

- Uncategorized (50)

- Vladimir Putin (4)

- Xi Jinping (2)

- Yemen (24)

Links

archives

- November 2021

- January 2021

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- October 2019

- July 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- July 2010

- June 2010

- May 2010

- April 2010

- March 2010

- February 2010

- January 2010

- December 2009

- November 2009

- October 2009

- September 2009

- August 2009

- July 2009

- June 2009

- May 2009

- April 2009

- March 2009

- February 2009

- January 2009

- December 2008

- November 2008

- October 2008

- September 2008

- August 2008

- July 2008

meta

The fallout from the 2005 Access Hollywood video published by the Washington Post Friday showing Donald Trump making crude sexual remarks and bragging in obscene language about sexually forcing himself on women, has plunged the Republican Party into “an epic and historic political crisis” as a growing number of prominent Republicans call on Trump to drop out of the race (“GOP consumed by crisis as more Republicans call on Trump to quit race” by Jenna Johnson and Robert Costa, Washington Post, Oct. 8, 2016).

In this video from 2005, Donald Trump prepares for an appearance on ‘Days of Our Lives’ with Access Hollywood host Billy Bush and actress Arianne Zucker. (Obtained by The Washington Post)

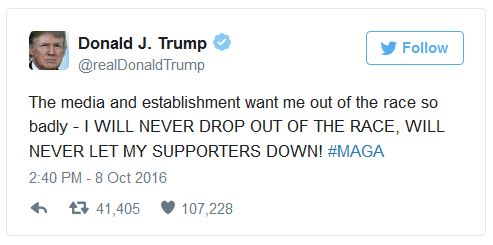

Trump, who offered “a qualified apology for the remarks” in a video statement, reportedly told the Post “he would not drop out under any circumstances.”

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) October 8, 2016

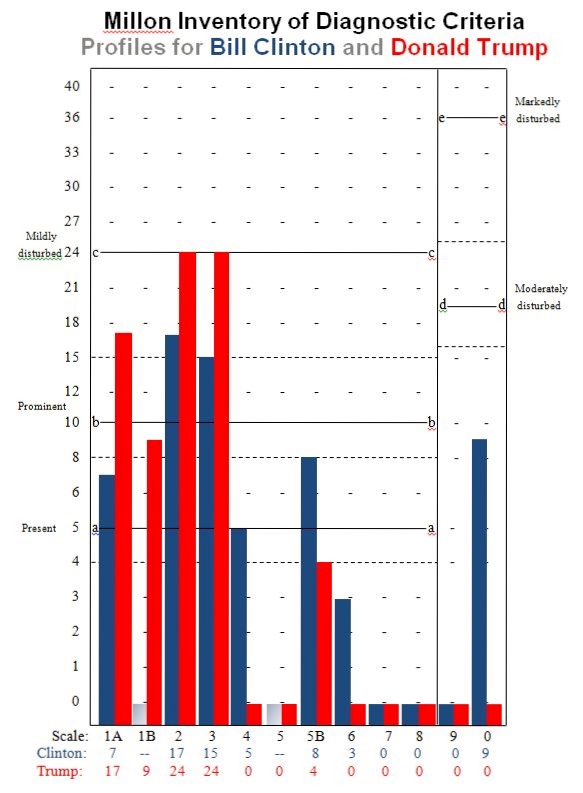

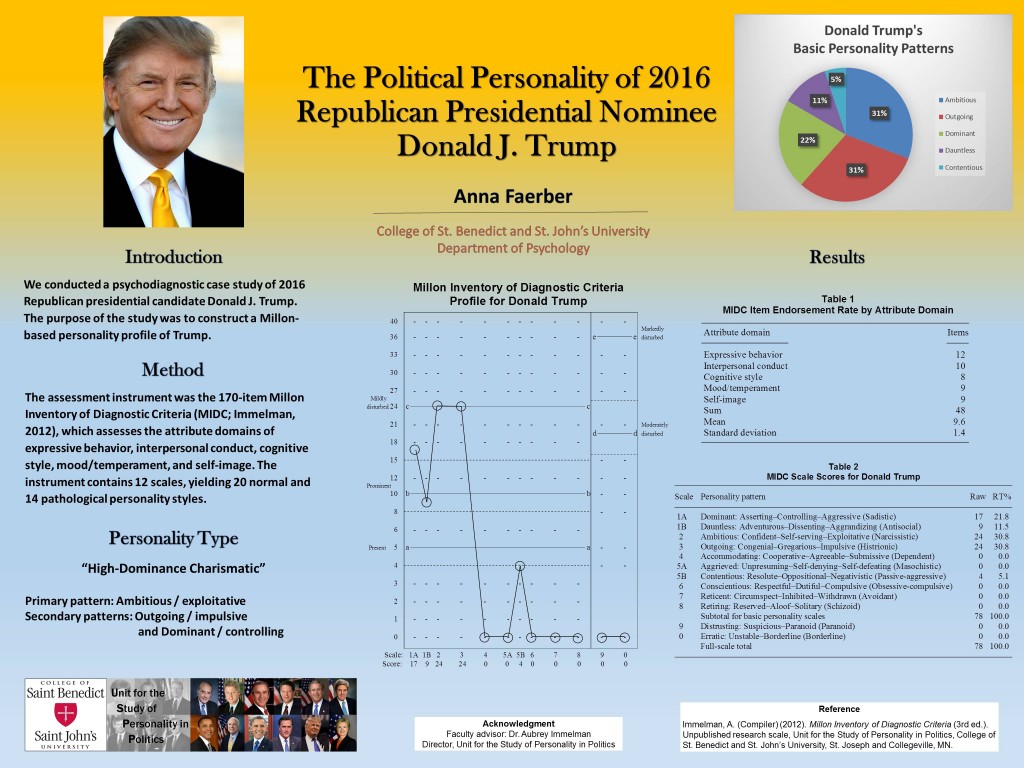

That is fully consistent with Trump’s personality profile, which for practical purposes is nearly identical (see figure below) to that of Bill Clinton, who was similarly defiant throughout his 1998-99 impeachment saga.

The major distinctions between Clinton’s and Trump’s profiles are that Trump is more dominant (aggressive, combative) than Clinton, who is more conflict averse (MIDC scale 1A: Trump = 17; Clinton = 7) and that Clinton is more accommodating than Trump, who is less agreeable (MIDC scale 4: Clinton = 5; Trump = 0).

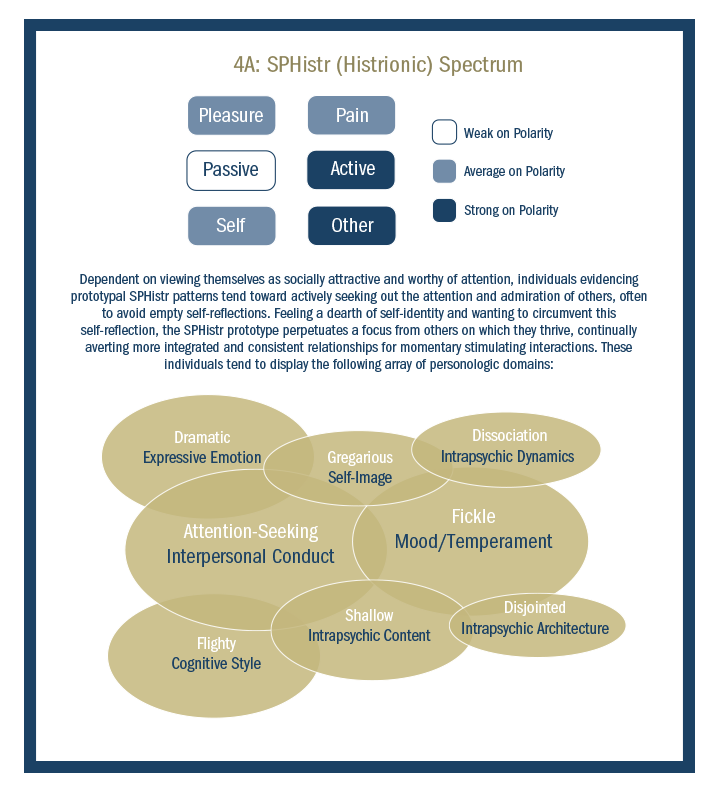

The key similarity between Trump and Clinton is their primary scale elevations on MIDC scales 2 and 3. Scale 2 (“Ambition”) is a measure of narcissism (Trump = 24, Clinton = 17) and Scale 2 (“Outgoing”) is a measure of impulsive, histrionic tendencies (Trump = 24, Clinton = 15).

The “amorous narcissism” of Bill Clinton and Donald Trump

According to psychologist Theodore Millon, Ph.D., a leading expert on personality and its disorders, the “distinctive feature” of the Ambitious-Outgoing personality composite, which he labeled the amorous narcissist, is an “erotic and seductive orientation” (Millon, 1996, p. 410).

For these personalities, sexual prowess serves to enhance self-worth: “It is the act of exhibitionistically being seductive, and hence gaining in narcissistic stature, that compels,” according to Millon — who adds that, because of their “indifferent conscience” and the pressing need to nourish their “overinflated self-image,” these individuals may “fabricate stories that enhance their worth” (Millon, 1996, p. 411).

Digging through the archives: Bill Clinton’s sexual misconduct and defiance redux

In the wake of the “Access Hollywood” firestorm, I revisited my “Clinton Chronicle” in the archives of the Unit for the Study of Personality in Politics to review my commentary, analysis, and prognostications regarding Bill Clinton, which in my opinion provide a predictive model for how Trump will handle the crisis.

This is what I found:

Do President Clinton’s “Sexual Dalliances” Feed His Male Ego?

By Aubrey Immelman

Sept. 27, 1998 — Tonight, on Fox News Channel’s “This Evening with Judith Regan,” psychologist Judy Kuriansky suggested that the kind of sexual dalliances in which President Clinton reputedly engaged with Monica Lewinsky “feeds a man’s ego.” Though I would not go so far as to cast all men in that mold, there is certainly theoretical support for Dr. Kuriansky’s contention with respect to some personality types – most notably the “amorous narcissist,” whose personality pattern is dominated by narcissistic and histrionic traits.

According to the literature on personality disorders, the “distinctive feature” of amorous narcissists is “an erotic and seductive orientation” (Millon, 1996, p. 410). For these personalities, sexual prowess serves to enhance self-worth; “it is the act of exhibitionistically being seductive, and hence gaining in narcissistic stature, that compels” (or “feeds a man’s ego,” to use Dr. Kuriansky’s turn of phrase). …

Virtually all indicators in Bill Clinton’s personality profile point to a will to fight impeachment and removal to the bitter end. …

Why Bill Clinton Will Not Resign

By Aubrey Immelman

Oct. 9, 1998 — Over the past two months I have been intrigued by the mounting tally of newspapers calling on President Clinton to resign. Not surprisingly, in view of his personality profile, Mr. Clinton is unfazed by those appeals. So certain are some commentators that the president will be unable to prevail that they have all but adopted the mindset of a compulsive gambler on a losing streak who steadfastly believes that his next wager will hit the jackpot.

With reference to the president’s fortunes in the face of revelations and accusations that stick to the president with all the tenacity of water on the back of a duck, Fox News Channel’s Bill O’Reilly, for example, has repetitively expressed the view, “One more thing, and he’s gone.” Perhaps O’Reilly’s unyielding faith in the improbable says more about himself – by all appearances a highly moralistic person with a well-developed sense of decency – than about Bill Clinton, whose inner experience of shame is vastly different.

In situations that would ordinarily elicit shame or humiliation, personalities such as Bill Clinton initially try to screen out negative and judgmental reactions through rationalization and denial, devising plausible “proofs” or alibis to present themselves in the best possible light to salvage their deflated self-esteem. When that fails, these personalities typically become defiant and, if necessary, unleash their self-bolstering rage. Reluctant contrition appears very late in their repertoire, when their confidence is shaken, and even then their experience of remorse or shame is but momentary.

President Clinton has the ability to be unperturbed by circumstances that would prompt most people to hang their head in shame. For that reason, I believe Mr. Clinton is unlikely to resign, unless so pressured by his party that his position becomes utterly untenable. But ultimately, there is no need even for a personality profile to understand why Bill Clinton is practically incapable of resignation: given his obsession with his legacy, it is inconceivable that Bill Clinton would meekly join the ranks of Richard Nixon in the history books as the only president to have resigned from office.

In conclusion, the only plausible scenario in which Donald Trump drops out of the race is if the Republican Party and its electorate abandon their support for Trump in toto.

Reference

Millon, T. (1996). Disorders of Personality: DSM-IV and Beyond (2nd ed.). New York: Wiley.

For more information, please consult the Unit for the Study of Personality in Politics Media Tipsheet at http://personality-politics.org/2016-election-media-tipsheet/

Related reports

The Political Personalities of 1996 U.S. Presidential Candidates Bill Clinton and Bob Dole (Aubrey Immelman, Leadership Quarterly, Vol. 9, No. 3, Special Issue: Political Leadership, Fall 1998, pp. 335–366).

A Comparison of the Political Personalities of 1996 U.S. Presidential Candidates Bill Clinton and Bob Dole (Paper presented by Aubrey Immelman at the 19th Annual Scientific Meeting of the International Society of Political Psychology, Vancouver, BC, June 30–July 3, 1996).

Related reports on this site

The Personality Profile of 2016 Republican Presidential Candidate Donald Trump (Aug. 9, 2015)

Click on image for larger view

Donald Trump’s Narcissism Is Not the Main Issue (Aug. 11, 2016)

© 2015 MILLON® (Click on images for larger view)

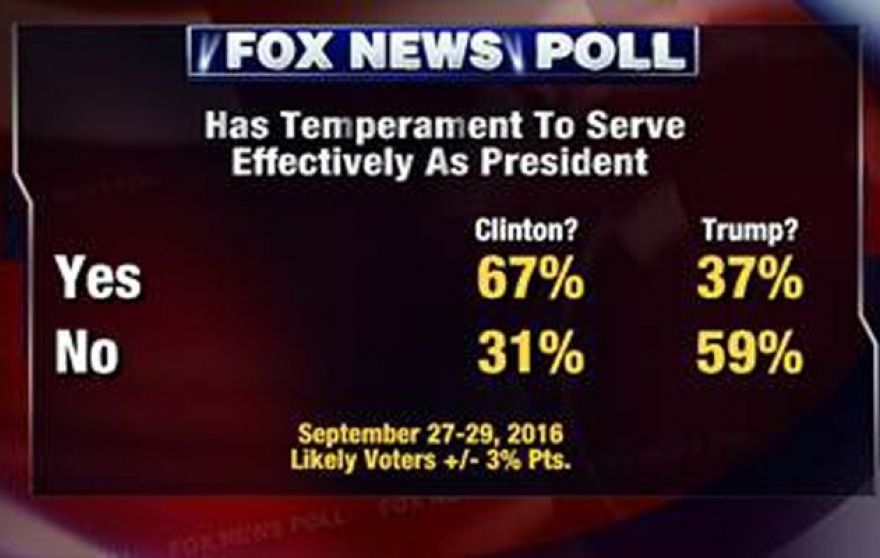

Donald Trump’s Temperament: Trump’s Fitness to be President (Oct. 5, 2016)

Related interest

The Man from Hope: Profiling Bill Clinton

How mental health professionals have sized up the president’s personality

By John Martin-Joy, M.D.

![]()

September 26, 2020

Excerpts with names of cited scholars bolded for emphasis

[ . . . ]

Even before impeachment, mental health professionals wasted no time in probing Clinton’s psychology. Beginning as early as 1994, psychologist David Winter was examining the content of Clinton’s major speeches for clues to his personality.

Clinton, Winter concluded, was an idealist who was motivated primarily by achievement. Such an orientation, however, tended to predict frustration rather than success in the presidency. In contrast, Winter asserted that power motivation—a love of the vicissitudes of the political process itself—was the best predictor of success. A playfulness like that of Franklin Roosevelt or John F. Kennedy was the royal road to political success.

A version of Winter’s assessment later appeared in Jerrold Post’s edited collection The Psychological Assessment of Political Leaders (2003). This remarkable volume probed Clinton’s psychology in depth. Contributors used a comparative approach (the book also examined Saddam Hussein of Iraq), drew on multiple sources, employed empirical rating scales, and in general deployed much professional rigor.

Going through the book today, one is struck by the depth and methodological care that the book’s contributors, all experienced in studying political leadership, brought to their task.

Psychiatrist and psychoanalyst Stanley Renshon, for example, explored what he saw as the central components of Clinton’s character: ambition, integrity, and relatedness. Using a psychodynamic approach and building on his own award-winning 1996 book, he postulated that Clinton’s character grew from his complex relationship with his mother Virginia. Renshon reviewed the Clinton marriage and identified Bill Clinton’s alleged ambition, impatience, persistence, and need to be special as important motives in his rise to power.

Psychoanalyst and political scientist Walter Weintraub looked closely at Clinton’s press conferences. In them, Weintraub found a high ratio of “I†and “me†statements to “we†statements, a ratio that to him suggested something distinctive: that Clinton saw himself as a leader who could get things done rather than the leader of an ideological crusade. Weintraub also saw a propensity in Clinton to assume “the victim role when attacked.†And Peter Suedfeld and Philip Tetlock looked closely at the quality of “integrative complexity” (flexibility, openness to ambiguity and to potentially conflicting ideas) as it applied to Clinton as decision-maker.

Renshon sounded a characteristic note of caution: In profiling public figures, “measured prudence†was preferable to “theoretical enthusiasm.â€

It was a warning that few psychological commentators on presidents would heed in the years ahead.

Psychologist John Gartner, an open enthusiast for an idea, used an altogether different approach in his later book In Search of Bill Clinton (2008). The book aimed for a general readership rather than an academic one. And it was the product of two years of deep immersion in Clinton’s world.

Gartner did not use empirical methods. Instead, he relied on extensive interviews. His project elicited cooperation from many friends and associates of Clinton’s, including staffers, friends of Clinton’s mother, and journalists who had covered the president for decades. In all, the psychologist conducted 100 interviews in an effort to understand the man. Gartner also had two brief public interactions with Clinton himself.

Gartner called his method “psycho-journalism.â€

Gartner’s idea was that Clinton had a “hypomanic temperament.†Explored at length in a previous Gartner book, the hypomanic temperament is a chronic high-energy state in which a person has “immense energy, drive, confidence, visionary creativity, infectious enthusiasm, and a sense of personal destinyâ€â€”not to mention impulsivity. Gartner carefully differentiated this temperament from similar-sounding relatives: a hypomanic episode and bipolar mania. He concluded that the hypomanic temperament is the key to Clinton’s striking combination of strength and vulnerability.

The argument was not unprecedented.

The hyperthymic personality, which appears similar to Gartner’s construct, is familiar to many clinicians. In 1996, psychologist Aubrey Immelman’s empirical research findings about Clinton [hyperlink added] suggested something arguably similar: an asserting/self-promoting and outgoing/gregarious personality type. In 2011 psychologist Dan McAdams, in comparing Clinton to George W. Bush, saw both as extraverts. And psychiatrist Nasser Ghaemi has long argued for the value of depression and bipolar disorder to some success in politics and in life. (In a review Ghaemi found Gartner’s previous book “one-dimensional” and superficial in its approach to bipolar disorder and related states.)

[ . . . ]

These efforts at psychological understanding from a distance, whatever their merits, have obvious limits.

Neither Post’s volume nor Gartner’s substantially addresses the ethics of evaluation from a distance. Yet none of Post’s contributors interviewed Clinton; none obtained his permission for their evaluations. Gartner’s two encounters with Clinton took place in public and lasted only a few seconds each: he shook hands with Clinton on one occasion and asked him one question on another.

Post himself is the profession’s major contributor to the question of the ethics of such comment. His argument, advanced elsewhere, is that the risks of comment on public figures must be weighed against the benefits to public education and public safety. For example, informing the public about a national danger related to a leader’s mental state may make the effort ethical. No such danger is documented in these books.

Bill Clinton’s fascinating complexity represented a turning point in the psychological evaluation of leaders from a distance in America. In the Clinton years and after, the practice of comment from a distance would become almost routine.

Admittedly, few of us can devote the time and care that Gartner devoted to his interviews and assessment of Bill Clinton. But more and more, the mental health professions continue to see clearly from a distance—and to try to get it right.

[ . . . ]

Full report at Psychology Today

John Martin-Joy, M.D., is a psychiatrist in private practice in Cambridge, Massachusetts. He is the author of Diagnosing from a Distance (Cambridge University Press, 2020) and a candidate at the Boston Psychoanalytic Society and Institute.

You must be logged in to post a comment.