Featured Posts

- Index of Psychological Studies of Presidents and Other Leaders Conducted at the Unit for the Study of Personality in Politics

- The Personality Profile of U.S. Supreme Court Associate Justice Brett Kavanaugh

- The Leadership Style of North Korean Leader Kim Jong-un

- North Korea Threat Assessment: The Psychological Profile of Kim Jong-un

- Russia Threat Assessment: Psychological Profile of Vladimir Putin

- The Personality Profile of 2016 Republican Presidential Candidate Donald Trump

- Donald Trump's Narcissism Is Not the Main Issue

- New Website on the Psychology of Politics

- Unit for the Study of Personality in Politics --- 'Media Tipsheet'

categories

- Afghanistan (228)

- Al Gore (2)

- Amy Klobuchar (4)

- Ayman al-Zawahiri (7)

- Barack Obama (60)

- Ben Carson (2)

- Bernie Sanders (7)

- Beto O'Rourke (3)

- Bill Clinton (4)

- Bob Dole (2)

- Campaign log (109)

- Chris Christie (2)

- Chuck Hagel (7)

- Criminal profiles (8)

- Dick Cheney (11)

- Domestic resistance movements (21)

- Donald Trump (31)

- Economy (33)

- Elizabeth Warren (4)

- Environment (24)

- George H. W. Bush (1)

- George W. Bush (21)

- Hillary Clinton (9)

- Immigration (39)

- Iran (43)

- Iraq (258)

- Jeb Bush (3)

- Joe Biden (13)

- John Edwards (2)

- John Kasich (2)

- John Kerry (1)

- John McCain (7)

- Kamala Harris (5)

- Kim Jong-il (3)

- Kim Jong-un (11)

- Law enforcement (25)

- Libya (18)

- Mahmoud Ahmadinejad (6)

- Marco Rubio (2)

- Michael Bloomberg (1)

- Michele Bachmann (173)

- Mike Pence (3)

- Military casualties (234)

- Missing person cases (37)

- Mitt Romney (13)

- Muqtada al-Sadr (10)

- Muslim Brotherhood (6)

- National security (16)

- Nelson Mandela (4)

- News (5)

- North Korea (36)

- Osama bin Laden (19)

- Pakistan (49)

- Personal log (25)

- Pete Buttigieg (4)

- Presidential candidates (19)

- Religious persecution (11)

- Rick Perry (3)

- Rick Santorum (2)

- Robert Mugabe (2)

- Rudy Giuliani (4)

- Russia (7)

- Sarah Palin (7)

- Scott Walker (2)

- Somalia (20)

- Supreme Court (4)

- Syria (5)

- Ted Cruz (4)

- Terrorism (65)

- Tim Pawlenty (8)

- Tom Horner (14)

- Tributes (40)

- Uncategorized (50)

- Vladimir Putin (4)

- Xi Jinping (2)

- Yemen (24)

Links

archives

- November 2021

- January 2021

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- October 2019

- July 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- July 2010

- June 2010

- May 2010

- April 2010

- March 2010

- February 2010

- January 2010

- December 2009

- November 2009

- October 2009

- September 2009

- August 2009

- July 2009

- June 2009

- May 2009

- April 2009

- March 2009

- February 2009

- January 2009

- December 2008

- November 2008

- October 2008

- September 2008

- August 2008

- July 2008

meta

A Formula for the Fall of Apartheid

Many factors combined to create a ‘perfect storm’

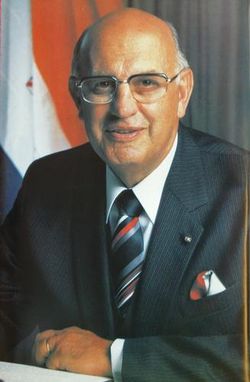

F. W. de Klerk and Nelson Mandela (Image: Public Domain)

By Aubrey Immelman

St. Cloud Times

December 15, 2013

Watching TV talking heads in the wake of Nelson Mandela’s passing, I could easily have been fooled into believing the former South African president would still be sitting behind bars on Robben Island, but for the efforts of these heroic politicians and assorted Reagan-era anti-apartheid activists.

I say “could,†because I knew better than to fall for facile explanations of South Africa’s transition from apartheid state to nonracial democracy.

That’s because I was blessed — or cursed — with the opportunity to observe the transition from a dual vantage point inside the regime: as a regional youth chair of the leading anti-apartheid opposition party working to effect change from within; and as a foot soldier in the apartheid government’s military pitted against Mandela’s guerrilla fighters in the armed struggle to topple the regime by force.

Factors accounting for change

So what exactly was it that caused apartheid to crumble? As is usually the case with complex historical events, a host of factors combined to form the “perfect storm†to end apartheid.

The most important elements were these:

Externally — the collapse of the former Soviet Union, the successful transition to majority rule in neighboring Namibia, and international sanctions against South Africa, including cultural isolation and economic divestment.

Internally — the liberation struggle, white opposition to apartheid, the failure of apartheid, moderation of the leadership in the ruling National Party, the breakdown of National Party hegemony and, finally, the personal role of the two leading players — Nelson Mandela and F. W. de Klerk, joint recipients of the Nobel Peace Prize in 1993.

» Collapse of communism: The 1989-91 collapse of communist governments in Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union — for many years the major sponsors of Mandela’s African National Congress — provided a strong incentive for the ANC to forgo the armed struggle in favor of seeking a negotiated settlement with the National Party government.

» Namibia’s transition to majority rule: Namibia, administered by South Africa since 1920 under a League of Nations mandate, gained independence in 1990 after protracted negotiations between the South African government and the black majority, ending a two-decades-long insurgency war. The peaceful transition played a significant role in allaying the fears of white South Africans with regard to power sharing.

» International sanctions: Coinciding with changes in Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union, punitive economic sanctions imposed by the international community were slowly sapping the South African economy, exerting pressure on the government to negotiate with (rather than fight) the ANC.

» The liberation struggle: Against the background of increasing economic and cultural isolation, the liberation struggle in South Africa drastically intensified during the mid-1980s. Internal resistance to apartheid took many forms, including consumer boycotts of white-owned businesses, rent boycotts in the black townships, nationwide strikes, and other forms of mass action designed to make the country ungovernable.

» Sustained pressure by the moderate white opposition: Though constituting a tiny minority in Parliament, the anti-apartheid opposition played an influential role in South African politics in the decade leading up to Mandela’s release from prison, garnering the support of up to 25 percent of white voters favoring its platform of a negotiated settlement with the black majority and universal franchise, popularly referred to as “One Man, One Vote.â€

» The failure of apartheid: A frequently ignored factor in the demise of structural apartheid is that its very fabric primed it for self-destruction in a modern world. Just as the feudal system in Europe succumbed to the modern nation state, apartheid as conceptualized by its architects in the 1950s and ‘60s became a political dinosaur. The apartheid system simply could not be sustained in a modern, industrialized, global economy.

» Moderation of the National Party leadership: By the 1970s the writing already was on the wall for apartheid, as the ruling National Party haltingly began to liberalize its policies. As a consequence of these accommodations, the ruling party’s right wing split off twice — in 1969 and again in 1982 — to form more conservative, “ideologically pure†opposition movements. An important implication of this realignment is that the ideological center in the National Party shifted to the left, creating new opportunities for the emergence of moderate leaders like de Klerk.

» The breakdown of National Party hegemony: Relentless international sanctions and isolation, the breakdown of apartheid policies, internal opposition, and the weakening of the old National Party with defections to the right and left all contributed to a breakdown of four decades of National Party hegemony.

And with Soviet communism consigned to the dustbin of history, the climate was ripe for a new world order.

As the 1980s drew to a close, the stage was set. What remained was for an event-making, forward-looking, conciliatory leader to step up to the plate. F. W. de Klerk was to be that man, with Nelson Mandela waiting in the wings.

———

Note

An unabridged version of this article, including an overview of South Africa’s political history, a summary of apartheid legislation, and psychological profiles of South African presidents P.W. Botha, F.W. de Klerk, and Nelson Mandela, is available at the link below.

Immelman, A. (1994). South Africa’s Long March to Freedom: A Personal View. The Saint John’s Symposium, 12, 1-20.

South Africa’s Transition from Apartheid to Nonracial Democracy

The Apartheid State: P. W. Botha

South African Transition: F. W. de Klerk

The New South Africa: Nelson Mandela

South Africa’s Long March to Freedom: A Personal View

By Aubrey Immelman

Abstract

In this article I first offer a brief historical account of European white settlement, and ultimately political dominance, in southern Africa. Next, I outline how whites, and in particular Afrikaner-dominated National Party governments after 1948, achieved almost total subjugation of South Africa’s black majority through oppressive legislation and the calculated use of force. In that regard I enumerate some of the draconian laws enacted in the post-1948 apartheid state — laws that served as an impetus for black nationalism, anger, resistance, protest and, after 1960, armed struggle to achieve liberation from white oppression. Against this background, I examine salient factors accounting for South Africa’s relatively peaceful transition from apartheid state to nonracial democracy, focusing on situational variables as well as the personal characteristics of South African presidents P. W. Botha, F. W. de Klerk, and Nelson Mandela.

Citation

Immelman, A. (1994). South Africa’s long march to freedom: A personal view. The Saint John’s Symposium, 12, 1-20.

F. W. de Klerk and Nelson Mandela

By Aubrey Immelman

Abstract

The purpose of this paper is to examine salient factors accounting for South Africa’s relatively peaceful transition from apartheid state to nonracial democracy, focusing on the political personalities of South African leaders P. W. Botha, F. W. de Klerk, and Nelson Mandela. Following a brief overview of situational variables, the paper describes the political personalities of Mandela and De Klerk as assessed by the Millon-Type Political Personality Checklist (MPPC). The study shows that one cannot fully account for political developments in South Africa’s transition without considering (a) the interaction between situational variables and the political personalities of Nelson Mandela and F. W. de Klerk and (b) synergistic features in the personalities of these two leaders.

Citation

Immelman, A. (1994). South Africa in transition: The influence of the political personalities of Nelson Mandela and F. W. de Klerk. Paper presented at the 17th Annual Scientific Meeting of the International Society of Political Psychology, Santiago de Compostela, Galicia, Spain, July 11–14, 1994.

A different view of Mandela and De Klerk

A Millon-Based Study of Political Personality: Nelson Mandela and F. W. de Klerk

Part I: Method and Preliminary Results

By Aubrey Immelman

Abstract

This paper reports the method and preliminary findings of an investigation of the political personalities of South African president F. W. de Klerk and African National Congress president Nelson Mandela. The purpose of the study was to assess the utility of Theodore Millon’s personological model as an alternative or supplementary conceptual framework and methodology for the assessment of political personality. Conceptually, the investigation was conducted from the perspective of a model of personality compatible with Axis II of DSM-III-R, which serves as an important psychodiagnostic frame of reference for the practice of contemporary psychiatry and clinical psychology. Methodologically, the investigation involved personality appraisals at a distance, using an instrument adapted from the work of Millon and his associates.

Citation

Immelman, A. (1993). A Millon‑based study of political personality: Nelson Mandela and F. W. de Klerk. Part I: Method and preliminary results. Paper presented at the 16th Annual Scientific Meeting of the International Society of Political Psychology, Cambridge, MA, July 6–11, 1993.

A Millon-Based Study of Political Personality: Nelson Mandela and F. W. de Klerk

Part II: Further Results and Implications

By Aubrey Immelman

Abstract

This paper reports the results of a psychobiographical investigation, using the Millon-Type Political Personality Checklist, of the political personalities of outgoing South African president F. W. de Klerk and newly elected South African president Nelson Mandela, and examines the interactional influence of their respective personalities in facilitating South Africa’s transition from apartheid state to nonracial democracy.

Citation

Immelman, A. (1994, June). A Millon-based study of political personality: Nelson Mandela and F. W. de Klerk. Part II: Further results and implications. Unpublished manuscript.

Related reports on this site

Nelson Mandela at 93 (July 18, 2011)

Passing of a Visionary Leader (May 16, 2010)

Farewell to a Hero (Jan. 2, 2009)

You must be logged in to post a comment.